Why Some Clocks Use IIII Instead of IV: The Mystery Explained

If you’ve ever looked closely at a traditional clock face with Roman numerals, you might have noticed something unusual: instead of “IV” for the number 4, it shows “IIII.” This small detail has puzzled and intrigued people for centuries. At first glance, it seems like a mistake. After all, the standard Roman numeral for 4 is IV, right? So why do so many clocks—especially classic ones like grandfather clocks, tower clocks, and luxury watches—use IIII?

This question has sparked debates among historians, horologists (clock experts), and designers. The answer, as it turns out, is not simple. There isn’t just one explanation, but rather a combination of historical, aesthetic, cultural, and even superstitious reasons. In this article, we’ll explore all the major theories and explain why IIII still appears on so many clock faces today.

The Basics: Roman Numerals and the Standard System

Before diving into the reasons, let’s recap how Roman numerals work. Roman numerals are made up of the letters I (1), V (5), X (10), L (50), C (100), D (500), and M (1000). Normally, 4 is written as IV, which is the subtractive form (5 – 1 = 4).

However, some early Roman texts and inscriptions used additive notation instead, so 4 could also be written as IIII. While subtractive notation became the standard over time, both forms were used interchangeably in certain contexts. This historical flexibility opens the door for multiple valid uses of IIII.

Theory 1: Aesthetic Balance on the Clock Face

One of the most widely accepted explanations is visual symmetry. A clock face is a circle divided into 12 equal parts, and designers often strive for visual balance.

Let’s look at the two halves of a traditional Roman numeral clock:

- On the right side: I, II, III, IIII

- On the left side: VIII, IX, X, XI, XII

Using IIII instead of IV gives the first four numbers a consistent rhythm (all beginning with I). This balances out the heavier V, X, and other numerals on the opposite side. If you were to use IV, the left side would visually dominate the right, making the design feel lopsided.

The inclusion of IIII creates a more even distribution of characters and improves the readability and harmony of the dial.

Theory 2: Historical Precedence and Tradition

The use of IIII predates modern clockmaking. In ancient Rome, many inscriptions and monuments used IIII instead of IV. This might be because the subtractive system was not fully standardized or simply because it was easier for readers to understand additive logic.

Clockmakers in the Middle Ages and Renaissance may have adopted this tradition as a nod to classical antiquity. Once the pattern was established, it became a respected standard in horology (the study and making of clocks).

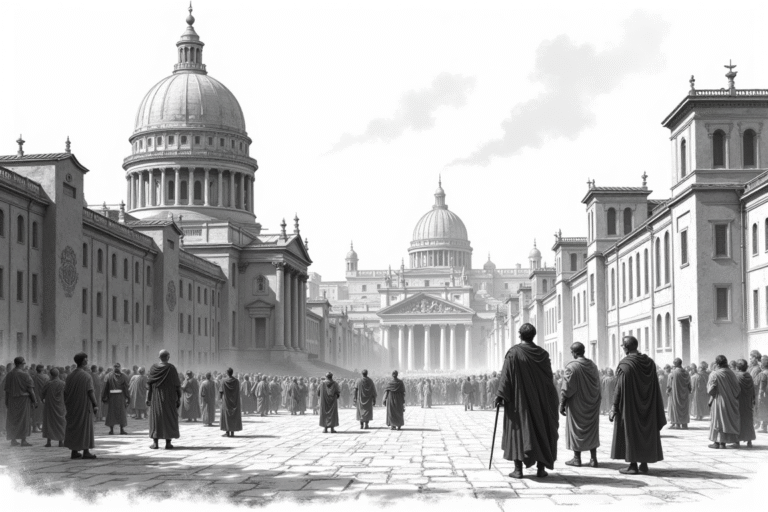

Famous tower clocks like Big Ben in London and the Prague Astronomical Clock use IIII, showing that this convention was long accepted by artisans across Europe.

Theory 3: Avoiding Confusion with the Roman God Jupiter

Another theory connects the use of IIII to Roman religion and superstition. In Latin, the Roman god Jupiter was spelled “IVPPITER” (the “U” was written as “V”).

Some historians believe that early Christians or conservative Romans avoided writing “IV” because it resembled the abbreviation for Jupiter. By using IIII instead, they could avoid invoking the name of a pagan deity, especially in religious or official contexts.

Although this theory is debated, it highlights how religion and politics influenced language, and possibly even how numbers were written on clocks.

Theory 4: Simplicity in Manufacturing and Reading

In the early days of clockmaking, every numeral had to be individually cast, engraved, or painted by hand. Using four “I” characters (which are simple straight lines) might have been more practical and cost-effective than crafting a unique “V.”

From a readability standpoint, IIII is also more easily recognizable at a glance than IV, especially for those unfamiliar with Roman numerals. On a quickly moving clock hand, three or four vertical lines stand out more clearly.

This could explain why IIII became popular in public clocks or town square timepieces meant to be easily readable from a distance.

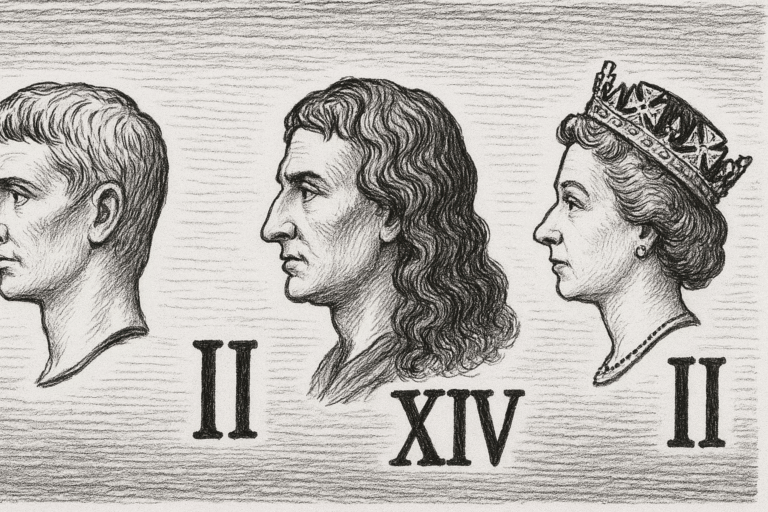

Theory 5: The Influence of Royalty and Tradition

One story tells of King Louis XIV of France insisting that IIII be used instead of IV on all clocks made in his court. When a clockmaker questioned this choice, the king allegedly replied that it looked better and that it should remain as is.

Whether this story is true or not, it reflects the impact of cultural authority and royal preference in shaping design trends. Once influential courts and guilds accepted the use of IIII, clockmakers across Europe followed suit.

In many cases, horological traditions are passed down through generations. Clockmakers may have kept the use of IIII simply because it was considered the correct or expected style.

Theory 6: Easier to Maintain Symmetry in Casting

Clocks were often made with molds that were reused across different designs. Having four I’s allowed for uniform casting and symmetry, particularly when the numerals were embedded into the metal. Casting a consistent set of characters reduced errors and kept production costs low.

From a mechanical production point of view, using IIII made logistics easier, since the same character (I) was used multiple times, reducing the need to create and store molds for V’s that weren’t used as often.

A Closer Look at Numeral Distribution

There’s also a compelling mathematical and design-based reason behind the choice. On a typical Roman numeral clock face:

- I appears 5 times: I, II, III, IIII, VIII

- V appears 4 times: V, VI, VII, IV or IIII

- X appears 4 times: X, IX, XI, XII

Using IIII instead of IV increases the number of “I” characters to balance visually with the number of V’s and X’s. It creates a kind of symmetry in frequency and distribution.

Clock designers understood that even minor changes in type balance affect the overall feel and clarity of a dial, especially in analog formats.

Regional and Style Differences

Not all clocks use IIII. Some modern or minimalist designs stick with IV. Digital clocks and text-based displays also follow standard Roman numeral conventions.

However, many classical or decorative clocks, especially those designed in the Gothic, Baroque, or Renaissance style, keep the IIII. Luxury watchmakers like Rolex, Cartier, and Patek Philippe often use IIII for visual heritage and luxury appeal.

Is It Wrong to Use IIII?

Technically, no. Both IIII and IV are correct in Roman numeral history. While IV is now the standard in most written contexts, IIII remains acceptable in horology. It’s not a mistake but a stylistic and traditional choice rooted in centuries of clockmaking practice.

In fact, some educational tools even teach both versions to explain how numerals evolved. This approach encourages learners to understand that language and symbols adapt to context and cultural use.

Modern Usage and Legacy

Today, you’ll still find IIII on:

- Grandfather clocks

- Tower clocks

- Pocket watches

- Classical-style wall clocks

- Historical monuments

It remains a subtle but iconic feature that tells you the designer valued tradition, balance, and readability. It also adds a sense of timelessness and elegance that connects modern craftsmanship with centuries of artistic heritage.

Conclusion

So, why do some clocks use IIII instead of IV? The short answer is: for many reasons. Visual balance, tradition, readability, simplicity, superstition, and history all play a role. The use of IIII may seem strange today, but it has a long and respected place in the world of horology.

It’s a reminder that design is not always about strict rules. Sometimes it’s about harmony, heritage, and human preference. The next time you glance at a clock with IIII, you’ll see more than just a number—you’ll see a window into history, tradition, and timeless craftsmanship.

Whether you’re designing a clock, buying a luxury watch, or teaching Roman numerals, this small but powerful detail shows how thoughtful design choices echo across centuries.